Origin: Chinese Buddhism, East Asian Buddhism, Chinese folk religion, Pure Land Buddhism.

Commonly associated with: mercy, compassion, kindness, unconditional love, protection, mothers, children, maternity, seamen, fishermen.

Name Meaning: “The One Who Observes the Sounds of the World”, “She Who Sees and Hears the Cries of the Human World”.

Other names: Guan Yin, Kuan Yin, Kuan Im, Kwan Yin, Kannon, Mother Guanyin.

Role: Mother Goddess, principle of compassion and unconditional love, bodhisattva, patroness of mothers and seamen, protectress of the welfare of all beings, protectress of women and children, protectress of earthly and spiritual travel.

*

Draped in white, standing atop a lotus flower with a water vase in her hand, Guanyin (觀音)—also spelled Guan Yin or Kuan Yin—is the beloved Chinese goddess of mercy and physical embodiment of compassion. All-seeing and all-hearing, she is characterized by her infinite benevolence and dedication to protecting those who are suffering.

Her name is a shortened version of Guanshiyin, which means “[The One Who] Observes the Sounds of the World”, or “She Who Sees and Hears the Cry from the Human World”, i.e., she who hears prayers. Guanyin is a bodhisattva—a Buddhist deity who has attained the highest level of enlightenment, but who, out of compassion, refrains from entering nirvana to remain engaged in the world and help all sentient beings.

*

Legends about Guan Yin first appeared in the Middle Kingdom more than two thousand years ago. Her popularity exploded around the Song Dynasty (960–1279), and she continues to be hailed and worshipped as the Goddess of Mercy to this day. Popular stories about Guan Yin involve her transforming into unassuming characters to bring help to troubled people.

Along with her role as goddess of mercy and compassion, Guanyin is also considered a Mother Goddess, a protectress of children, a goddess of fertility and motherhood. She is surnamed Sung-Tzu-Niang-Niang, “lady who brings children.” Worshiped especially by women, this goddess comforts the troubled, the sick, the lost, the senile, and the unfortunate. Her popularity has grown such through the centuries that she is now also regarded as the protector of sailors, farmers, fishermen and travelers. She cares for souls in the underworld, and is invoked during post-burial rituals to free the soul of the deceased from the torments of purgatory. Guanyin, Buddhists believe, can recognize the cries of all those who suffer on earth and guide them towards salvation.

*

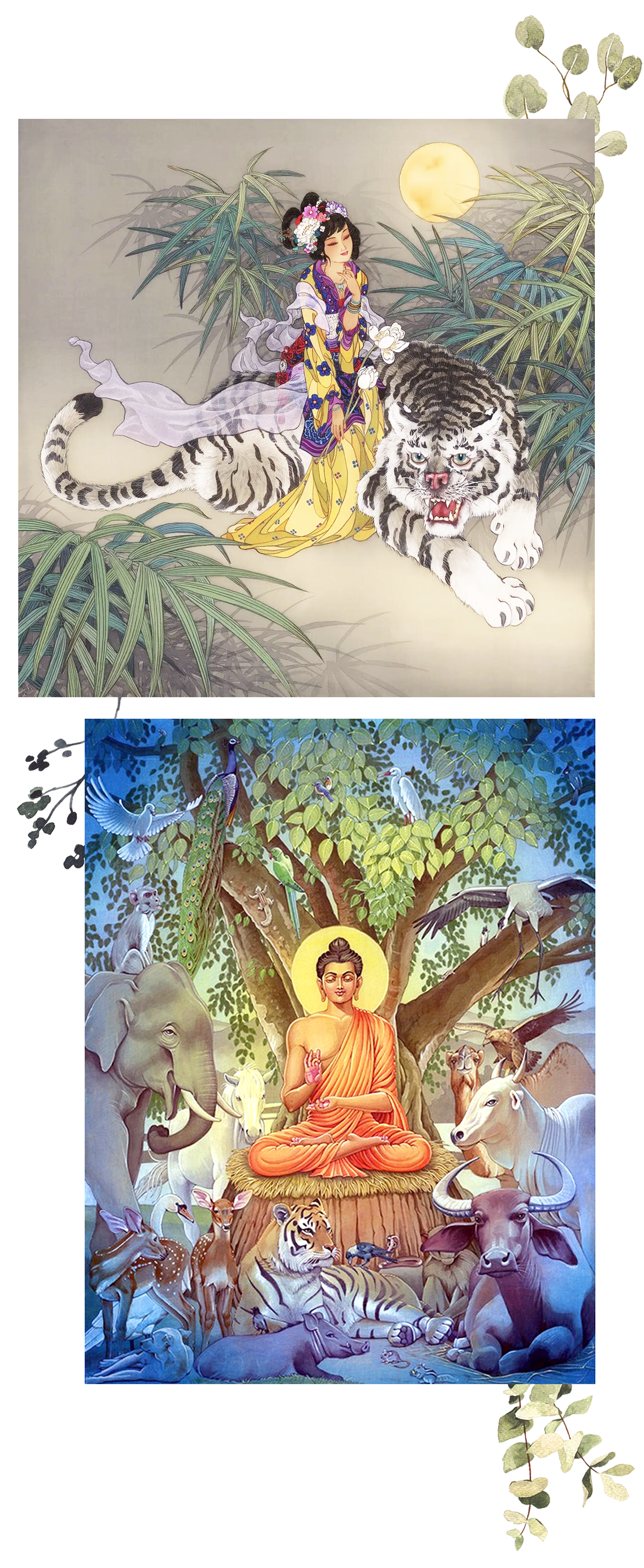

Guanyin is originally based on Avalokiteśvara, the male bodhisattva who embodies the compassion of all Buddhas. Avalokiteśvara’s myth spread throughout China and East Asia, and mixed with local folklore in a process known as syncretism (the combining of different religions, beliefs, or schools of thought) to become the modern-day understanding of Guanyin. Representations of Guanyin in China before the Song dynasty were masculine in appearance, but gradually adopted feminine attributes. Though she can take both male and female forms, Guanyin is most often represented as a woman in Chinese lore, although some people believe her to be androgynous, or without gender.

Because she is considered the personification of compassion and kindness, a Mother Goddess and patron of mothers, Guanyin’s representation in China was further interpreted in an all-female form around the 12th century. On occasion, Guanyin is also depicted holding an infant to further stress the relationship between the bodhisattva, maternity, and birth. In the modern period, Guanyin is most often represented as a beautiful, white-robed woman.

*

*

An origin story of Guanyin in Chinese folklore is the tale of Princess Miao Shan. Long ago, in a small Chinese state, a king had three daughters and wanted to marry them off to suitable families. Yet the youngest princess, Miao Shan, had a different wish. She wanted to become a Buddhist nun and devote herself to the needy. Enraged, the king disowned his daughter and sent her into exile. He was cruel and self-righteous, and ordered for his youngest daughter to be killed multiple times, but she always found refuge among those she helped, and was able to carry out her spiritual practice and service to the underprivileged.

Years passed, and the king became deathly ill, having accumulated terrible karma during his cruel reign. An old monk visiting the kingdom told him, “To be cured, you must ingest a potion distilled from the arms and eyes of one who is willing to give them freely.” Desperate, the king implored his older daughters, who were unwilling to help. The monk offered, “On top of Fragrant Mountain lives a bodhisattva of compassion. Send a messenger to her to plead for deliverance.”

*

*

This wandering monk proved to be none other than a transformation of Miao Shan. After years of arduous spiritual practice, she had become a bodhisattva. Having heard of her father’s trouble, she morphed into the monk to advise him. Then at the temple, she received her father’s messenger in her true form and told him, “This illness is punishment for past sins. But as his daughter, it is my duty to help.” She then removed her eyes and severed her arms for the messenger to take back.

Back in the kingdom, the old monk reappeared to concoct the magical elixir that gave the king a miraculous recovery. The king was extremely grateful to the monk, who simply replied: “Best thank the one who made this sacrifice for you.”

So the king traveled to Fragrant Mountain. There, he was shocked to see his daughter presiding over hundreds of followers, and without arms and eyes. Tears fell from his eyes as he came to realize all she must have suffered. Miao Shan received him benevolently, and bade him to live with compassion and practice Buddhism. Then, a flash of light engulfed them all as she transformed into the divine image of a bodhisattva with eyes and arms restored. Grateful at her exceptional benevolence and lack of rancor, the king begged for his daughter’s forgiveness and in a gesture of atonement, ordered statues to be made of her and placed across his kingdom.

In some versions of this legend, Guanyin manifested with one thousand eyes and one thousand arms—all the better for reaching out to all who suffer in the world.

*

Guanyin is often referred to as the most widely beloved Buddhist Divinity, with miraculous powers to assist all those who pray to her. Some Buddhists believe that when they depart from this world, they are placed by Guanyin in the heart of a lotus, and then sent to the western pure land of Sukhāvatī, a celestial realm in Mahayana Buddhism.

Several large temples in East Asia are dedicated to Guanyin. She has several abodes or mythical dwellings associated with her, also called bodhimanda, a term used in Buddhism meaning the “position of awakening”, “a place used as a seat, where the essence of enlightenment is present”. Bodhimandas are spiritually pure places conducive to meditation and enlightenment, regularly visited by Buddhist pilgrims. Guan Yin has bodhimandas and pilgrimage centers all around East Asia, including in India, China, Korea, Japan, Tibet, Nepal, Burma, Thailand and Sri Lanka, with her main pilgrimage site located in China.

*

*

In Pure Land Buddhism, a branch of Mahayana Buddhism widely practiced in East Asia, Guanyin is described as the “Barque of Salvation”. She is believed to temporarily liberate beings out of the Wheel of Samsara into the Pure Land, where they will have the chance to attain Buddhahhood.

Even among Chinese Buddhist schools that are non-devotional, Guanyin is still highly venerated. Instead of being seen as an active external force of unconditional love and salvation, the character of Guanyin is revered as the principle of compassion, mercy and love itself. The act, thought and feeling of compassion and love is viewed as Guanyin herself. A merciful, compassionate, loving individual is said to be Guanyin. A meditative or contemplative state of being at peace with oneself and others is seen as Guanyin.

*

*

No other figure in the Chinese pantheon appears in a greater variety of images—there are thousands of different incarnations or manifestations of Guanyin. The Lotus Sutra, one of the most popular sacred texts in the Buddhist canon, describes thirty-three specific manifestations that Guanyin can assume to assist other beings seeking salvation. Guanyin is a widely depicted subject of Asian art and is found in the Asian art sections of most museums in the world.

One representation of Guanyin depicts her with a serene expression in a relaxed position known as “royal ease”, on a stylized mountain or rock—a symbol of the deity’s readiness to rise at any moment from a state of deep contemplation to help other beings. The name of this particular representation, Water Moon Guanyin, appears after the 1100s and refers to a chapter in the Avatamsaka Sūtra (Flower Garland Sutra). The text tells how Guanyin sits in a rocky cave meditating on the reflection of the moon on the water, a metaphor for the illusory nature of all things and a reminder not to be overly attached to earthly matters. This representation can be read as male or female, which indicates Guanyin’s universal and inclusive nature.

*

In China, Guanyin is usually depicted as a barefoot, young gracious woman dressed in flowing white robes, symbolizing purity, peace, and harmony. She stands tall and slender, a figure of infinite grace, her gently composed features conveying the sublime selflessness and compassion that have made her the favorite of all deities. She may be seated on an elephant, standing on a fish, nursing a baby, holding a basket, having six arms or a thousand, and one head or eleven.

Guanyin is frequently portrayed sitting on a lotus flower, the Buddhist symbol of purity of the body, speech, and mind. She is typically holding a water jar in her right hand, representing compassion and wisdom. In her left hand, she holds a willow branch to sprinkle divine nectar on life to bless people with physical and spiritual peace. The willow branch is also a symbol of adaptation as it can bend without breaking and is used for medicinal purposes.

*

Guanyin is often represented on the back of a dragon, the ancient symbol of spirituality, wisdom, and the power of transformation. Her crown usually depicts the image of Amitābha, a celestial Buddha considered to be her spiritual teacher. The dove flying behind her represents abundance of fertility. The jade necklaces she wears, symbolic of Indian and Chinese royalty, contain beads that represent all living things. If a book or scroll is pictured with Guanyin, it represents the teachings of Buddhism.

Guanyin is often depicted either alone, or flanked by two children or two warriors. The two children are her acolytes who came to her when she was meditating at Mount Putuo. The girl is known as Longnü (Jade Maiden) and the boy Shancai (Golden Youth). The two children also represent her bestowing children in homes and temples. The two warriors are the historical general Guan Yu from the late Han dynasty and the bodhisattva Skanda.

*

In a portrayal known as the Child-Sending Guanyin, she is represented holding an infant. Considered the patron saint of mothers, Guanyin is believed to have the ability to grant parents children. Another popular depiction of Guanyin—particularly in the region of Fujian—represents her as a maiden carrying a fish basket. This particular representation of the goddess is called Yulan Guanyin, the patron saint of fishermen.

Other representations of Guanyin known as “Thousand-Armed Guanyin” (or “Guanyin as Great Compassion”) and “Eleven-Headed Guanyin” (or ‘Guanyin of the Universally Shining Great Light’) show her with many arms, or many heads. One legend says that after struggling to understand the needs of so many, her head split into 11 pieces, which the Buddha turned into 11 full-sized heads. When she tried reaching out to help all who needed it, her arms split into a thousand pieces, which the Buddha turned into a thousand arms.

*

*

*

Due to her symbolization of compassion, Guanyin is associated with vegetarianism in East Asia. Buddhist and Chinese vegetarian restaurants are generally decorated with her image, and she appears in most Buddhist vegetarian pamphlets and magazines.

Vegetarianism is practiced by significant portions of Mahayana Buddhist monks and nuns, as well as laypersons. In Buddhism, the views on vegetarianism vary between different schools of thought, although vegetarianism is generally encouraged. The Mahayana schools generally recommend a vegetarian diet because the Buddha outlined in some of the sutras that his followers must not eat the flesh of any sentient being.

All Buddhist ethical teachings are concerned with our relationship to “all beings,” “living beings,” or “sentient beings.” These terms in Buddhism are employed deliberately to include animals within the scope of Buddhist compassion. Buddhism teaches boundless compassion for all sentient beings, a compassion that expresses itself through nonviolence toward all.

*

In the Mahayana Mahaparinirvaṇa Sutra, a text giving the Buddha’s final teachings, the Buddha insisted that his followers should not eat any kind of meat or fish. In several Mahayana sutras, the Buddha vigorously denounced the eating of meat, because such an act is linked to the spreading of fear amongst sentient beings and violates the bodhisattva’s fundamental cultivation of compassion. Moreover, the Buddha declared that since all beings share the same ‘Dhatu’ (spiritual Principle or Essence) and are intimately related to one another, killing and eating other sentient creatures is equivalent to a form of self-killing. The sutras which advocate for vegetarianism include the Mahayana Mahaparinirvaṇa Sutra, the Śurangama Sutra, the Brahmajala Sutra, the Aṅgulimaliya Sutra, the Mahamegha Sutra, and the Laṅkavatara Sutra.

*

*

Guanyin has often been called the Buddhist counterpart of the Virgin Mary, and comparisons between these two strikingly similar religious figures are often observed by both Christians and Buddhists.

During the Middle Ages—a period of over one thousand years—people of various cultures across the world practiced their religious faiths independently, while also maintaining cross-cultural exchange. Curiously, certain works of art in both western Christian and eastern Buddhist cultures seem to share incredible visual similarities. Both contexts produced images of divine motherly figures that represent concepts of compassion, mercy, and love: the Virgin Mary in medieval Europe, and Guanyin in imperial China.

Depictions of Guanyin holding a child in Chinese art and sculpture closely resemble the typical Catholic Madonna and Child painting. Both figures are embodiments of compassion, maternal love, mercy and forgiveness, and both are the patron saints of mothers.

*

These examples pose interesting questions about how pre-modern artists visualized different aspects of divinity in their respective cultural contexts. Christians and Buddhists understood the Virgin Mary and Guanyin in similar ways, despite the fact that they did not directly influence one another until later periods of Imperialism and Colonialism in Asia. These kindred representations illustrate how people across the world envision human emotions and philosophical concepts in similar ways, which suggests the existence of what Carl Jung called archetypes—universal patterns, primal symbols and images that are part of the collective unconscious. They are underlying base forms, a kind of innate knowledge derived from the sum total of human history, from which emerge images and motifs that manifest in comparable ways across different cultures, in this case, the image of the Mother.

*

Comparing works of art depicting the Christian Virgin Mary and the Buddhist Guanyin shows the universal compassion of divine maternal figures. Guanyin and the Virgin Mary fulfill a similar role: that of hearing us in our distress, meeting us with tenderness and strengthening us to face the tasks of life. The centrality of these maternal figures in both Buddhism and Christianity suggests that mature adults share moments of deep self-doubt, and longings to recover some of the security of childhood. These representations point to the importance of the archetype of the Mother across cultures, and the healing power of maternal, compassionate love in peoples’ everyday lives.

*

*

Here, you will find simple and gentle practices, prompts and rituals that will help you connect with the energy of Guanyin and embody her qualities.

*

*

Consider shifting your perspective from how others who up for you, to how you can show up for others. Reflect on the relationships in your life—have you tended to them with care? Seek out ways to water the people around you in the best way for their growth. Soon enough you’ll find yourself surrounded by a blooming garden.

Practice by modernmind

*

*

*

*

Listen to this 15-minute guided loving kindness meditation. Compassion meditation involves silently repeating certain phrases that express the intention to move from judgment to caring, from isolation to connection, from indifference to understanding. The practice involves bringing to mind different people (including yourself), and sending them loving-kindness and peace. You don't have to force a particular feeling or get rid of unpleasant or undesirable reactions; the power of the practice is in the wholehearted gathering of attention and energy, and concentrating on each phrase.

Notice how this practice makes you feel. What happened to your heart? Did you feel warmth, openness and tenderness? Did you have a wish to take away the other’s suffering? How does your heart feel different when you envision your own or a loved one’s suffering, a stranger’s, or a difficult person’s? Bask in the joy of this open-hearted wish to ease the suffering of all people and beings, and how this attempt brings joy, happiness, and compassion in your heart at this very moment.

Practice by Penny McGahey on Insight Timer

*

*

*

Even in the midst of suffering, it is possible to bring your awareness to the good qualities within yourself and allow them to manifest in your consciousness. Practice mindful breathing to remind yourself of your Buddha nature, of the great compassion and understanding in you. Follow this simple meditation below, aligning with the patterns of your breath:

1. Breathing in, I am aware that I am breathing in. Breathing out, I am aware that I am breathing out.

2. Breathing in, I am in touch with the energy of mindfulness in every cell of my body. Breathing out, I feel nourished by the energy of mindfulness in me.

3. Breathing in, I am in touch with the energy of solidity in every cell of my body. Breathing out, I feel nourished by the energy of solidity in me.

*

4. Breathing in, I am in touch with the energy of wisdom in every cell of my body. Breathing out, I feel nourished by the energy of wisdom in me.

5. Breathing in, I am in touch with the energy of compassion in every cell of my body. Breathing out, I feel nourished by the energy of compassion in me.

6. Breathing in, I am in touch with the energy of peace in every cell of my body. Breathing out, I feel nourished by the energy of peace in me.

7. Breathing in, I am in touch with the energy of freedom in every cell of my body. Breathing out, I feel nourished by the energy of freedom in me.

8. Breathing in, I am in touch with the energy of awakening in every cell of my body. Breathing out, I feel nourished by the energy of awakening in me.

Spiritual practice by Thich Nhat Hanh in Creating True Peace

*

*

Practice until you see yourself in the cruelest person on Earth, in the child starving, in the political prisoner.

Continue practicing until you recognize yourself in everyone in the supermarket, on the street corner, in a concentration camp, on a leaf, in a dewdrop. Meditate until you see yourself in a speck of dust in a distant galaxy. See and listen with the whole of your being.

If you are fully present, the rain of Dharma will water the deepest seeds in your consciousness, and tomorrow, while you are washing the dishes or looking at the blue sky, that seed will spring forth, and love and understanding will appear as a beautiful flower.

Spiritual practice by Thich Nhat Hanh

*

*

Through this beautiful guided audio journey, bring the qualities of a mountain to your meditation practice and life—stability, groundedness, patience, presence and deep wisdom. Allow the mountain to be your teacher. Our hearts can hold all of life’s ups and downs, the pain and darkness, the light and joy, as well as the mystery and wonder of life unfolding. May your inner mountain be your guide.

Pratice by Andy Hobson on Insight Timer

*

*

*

“Lokah Samastah Sukhino Bhavantu” is a Compassion or Loving-Kindness Mantra which translates to: “May all beings everywhere be happy and free, and may the thoughts, words, and actions of my own life contribute in some way to that happiness and to that freedom for all.” This mantra promotes compassion and living in harmony with all sentient beings.

Speaking or chanting this mantra is a prayer each one of us can practice every day. It reminds us that our relationships with all beings should be mutually beneficial if we ourselves desire happiness and liberation from suffering. No true or lasting happiness can come from causing unhappiness to others. No true or lasting freedom can come from depriving others of their freedom. If we say we want every being to be happy and free, then we have to question our own actions—how we live, how we eat, what we buy, how we speak, and even how we think. When we chant, speak or even think the words lokah samastah sukhino bhavantu, if we include all the other animals with whom we share this planet in our concept of “all beings,” including the animals we use for food, we can start to create the kind of world we want to live in—a kind world.

Source: Jivamukti Yoga

*

*

*

You can close your eyes or keep them opened for this micro-practice, that can be done any time throughout the day. Imagine the smile of divine mothers like Guan Yin or Mother Mary, this serene compassionate smile that is often seen on their faces. This gentle smile that communicates so much love and tenderness. Find an inner version of that smile. You don’t have to move your outer face at all. Smile inwardly at the back of your own heart. You can start to feel how the energy of that smile slowly begins to open your heart, to warm your heart. You can feel how the energy of that smile illuminates a very particular quality inside of the heart. The Inner Smile is a very ancient Qi Gong healing technique, because the energy of the smile contains this quality of infinite compassion. Smiling inwardly at your own heart can allow your own innocent heart to be revealed. Start to feel what gets touched here, what gets opened. What qualities inside of the heart are awakened? Find that inner smile any time throughout your day.

*

*

Dive deeper into the world of Guanyin, her practices, and the wisdom of Buddhism, with these resources including books, articles and podcasts.

-

✎ Book

‘The Way of the Bodhisattva’

by Shantideva -

✎ Book

‘Becoming Bodhisattvas: A Guidebook for Compassionate Action’

by Pema Chödrön -

✎ Book

‘Becoming Kuan Yin: The Evolution of Compassion’

by Stephen Levine -

✴ Journal Article

‘Kuan Yin and Tara : Embodiments of Wisdom-Compassion Void’

by John Blofeld -

✤ Illustrated Book

‘Kuan Yin: The Princess Who Became the Goddess of Compassion’

by Maya van der Meer & Wen Hsu -

❊ Podcast

‘Guanyin, Bodhisattva of Compassion’

by The Lonely Palette -

✎ Book

‘The Tibetan Book of the Dead’

by Graham Coleman & Thupten Jinpa (Ed.) -

✎ Book

‘Bodhisattva of Compassion: The Mystical Tradition of Kuan Yin’

by John Blofeld -

✎ Oracle Deck

‘Kuan Yin Oracle: Blessings, Guidance & Enlightenment from the Divine Feminine’

by Alana Fairchild -

✦ Article

‘Compassion, Mercy, and Love: Guanyin and the Virgin Mary’

by Kevin D. Pham -

✎ Book

‘The Kuan Yin Oracle: The Voice of The Goddess of Compassion’

by Stephen Karcher -

✎ Book

‘Buddhist Magic: Divination, Healing, and Enchantment through the Ages’

by Sam van Schaik -

✎ Book

‘The Heart of the Buddha's Teaching: Transforming Suffering into Peace, Joy, and Liberation’

by Thich Nhat Hanh -

✎ Book

‘Chinese Myths and Legends: The Monkey King and Other Adventures’

by Shelley Fu & Patrick Yee -

✎ Book

‘The Kuan Yin Chronicles: The Myths and Prophecies of the Chinese Goddess of Compassion’

by Martin Palmer, Jay Ramsay & Man-Ho Kwok -

✎ Book

‘The Wise Heart: A Guide to the Universal Teachings of Buddhist Psychology’

by Jack Kornfield