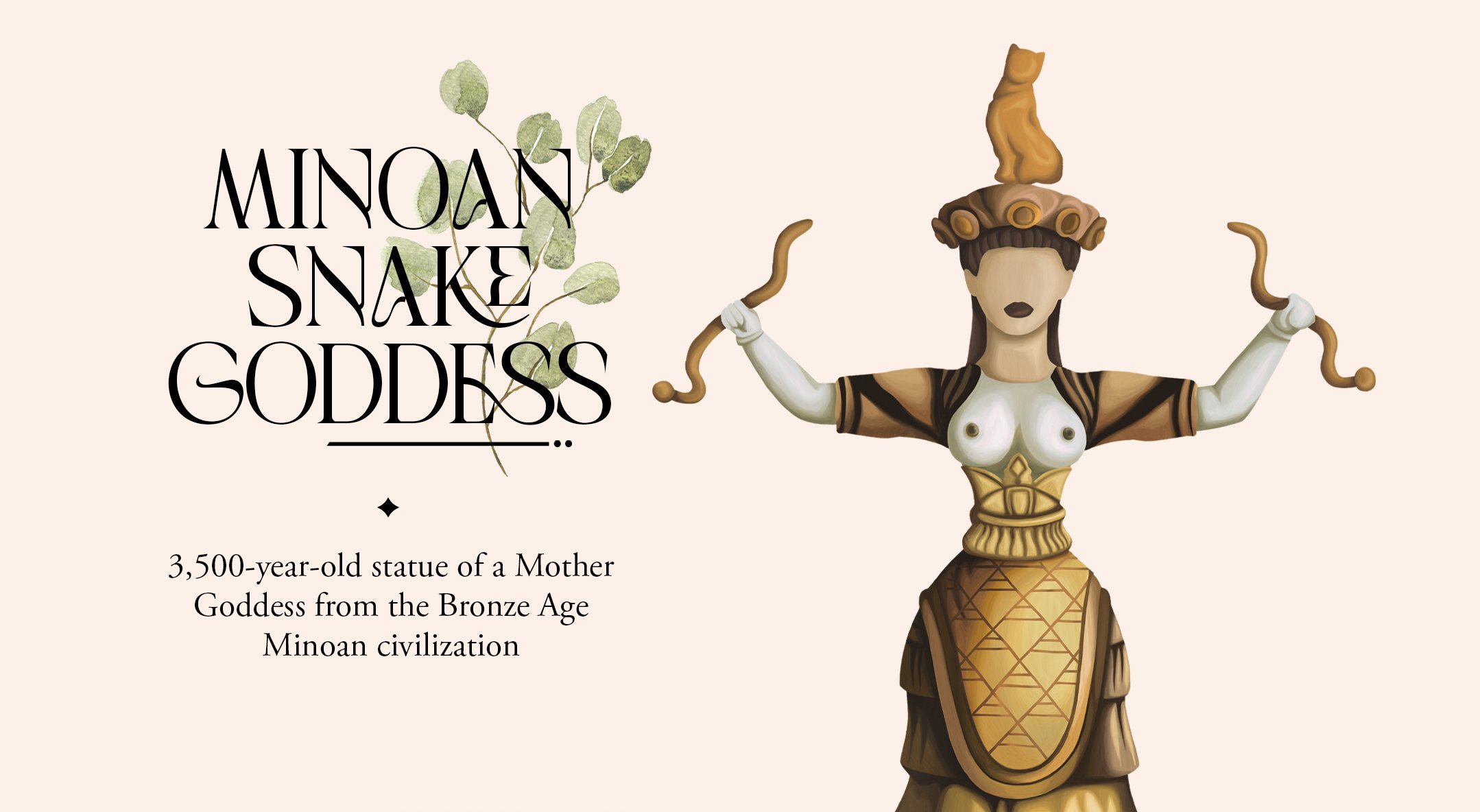

In 1903, English archaeologist Arthur Evans and his team found two snake goddess figurines in the Minoan palace at Knossos, in the Greek island of Crete, during a decades-long excavation program that greatly expanded knowledge and awareness of the Bronze Age Minoan civilization. The figures are now on display at the Heraklion Archaeological Museum.

The figurines date to near the end of the neo-palatial period of Minoan civilization, around 1600 BCE. They were extensively restored, and Evans called the larger of the figurines a "Snake Goddess", and the smaller a "Snake Priestess". Since then, it has been debated whether Evans was right, or whether both figurines depict priestesses, or both depict the same deity or distinct deities. The smaller figure, which is now also generally referred to as a "Snake Goddess", became a popular icon for Minoan art and religion.

Ever since the images of these figures were published, archaeologists, art historians, and feminist scholars have worked to determine their role and significance in Minoan culture. The combination of elaborate clothes, bare breasts and the intriguing snakes, attracted considerable publicity, and also the proliferation of various fakes.

The figurines are made of faience, a crushed quartz-paste material which after firing gives a shiny glass-like finish with bright colors. This material symbolized the renewal of life in old Egypt, thus it was used in funeral cults and sanctuaries. The smaller figure, as restored, holds two snakes in her raised hands, and on her headdress is a cat or panther. We will explore the symbolism of the snake in the section The Goddess and the Serpent.

Both goddesses have a knot between their breasts, resembling the sacral knot, an important Minoan symbol of holiness on figurines or cult-objects. It can be compared with the Egyptian ankh (eternal life), or with the tyet (welfare/life) a symbol of Isis (the knot of Isis).

*

While the statuette's true function is somewhat unclear, her exposed and amplified breasts suggest that she is probably some sort of fertility figure. Evans supported prevailing views about the existence of a Mother Goddess worship in the prehistoric era and so, when the Snake Goddess was found in 1903, he not only identified her as a "goddess" but also claimed that she was worshipped by the Minoans as an aspect of the Mother Goddess. Evans theorized that Minoans lived in a matrilineal, or even a matriarchal, society.

In many ancient cultures, a Mother Goddess (also referred to as Great Goddess) represents nature, motherhood, fertility, creation, destruction, or an embodiment of the bounty of the Earth. When equated with the Earth, such goddesses are sometimes called the Earth Mother.

The depictions of these Mother Goddesses are considered allegorical figures or personifications of the idea or concept of fertility. These representations are very common in prehistoric, stone age religions. In Crete, the uncovering of the breasts was a sacred gesture, symbolizing the nourishing lifestream of the Mother.

The Minoan Snake Goddess is also called "the goddess of the household", because a number of these types of figurines were found in house sanctuaries, and because the snake was regarded as the protector of the house in Minoan religion.

*

Thousands of years before the Bible was ever written, creation stories centered around a Goddess.

It is believed that the Great Goddess was worshiped among early agricultural peoples of the Mediterranean region and Southwest Asia. Her cult was perhaps carried to Crete in ancient times by settlers from Anatolia; or it might have originated in Africa.

The Great Goddess was worshipped in many forms throughout the Mediterranean, the Aegean, Turkey and the Near East, Northwest Africa and Europe through Neolithic times, until the Bronze Age. In Cretan culture, there were no figures of male gods.

*

Even into the male-dominated and war-ridden world of the Bronze Age, the Cretans—unlike most of their contemporaries—had no temple or temple-figures. Their sanctuaries were in nature, they worshiped among sacred trees. As G. Rachel Levy wrote, the Cretans developed a religion unusually detached from formal bonds, but emotionally binding in its constant endeavor to establish communion with nature's elements. Perhaps this was the reason why they never built temples, but performed their rites in nature—on mountain peaks, in caves, in rustic shrines. Their rituals aimed to preserve the peoples' relationship with the Earth.

The Cretans appear to have been gentle, joyous, sensuous and peace-loving. From the evidence of ruins, they maintained at least one thousand years of culture unbroken by war. The only other peoples we know of with such a long peace record—e.g., those of the Indus Valley and of Southern India—were also Mother Goddess cultures.

*

*

Crete was the last, full flowering of matriarchal culture. We are taught that Western civilization begins with Greece, but in fact the imagination of the Greeks came from Crete. All Greek religious rituals, all Greek mythology, was of Cretan-Mycenaean origin. Rites performed at Eleusis in utter secrecy were, in earlier Crete, celebrated in sacred groves. All these practices derived from the cult of the Great Goddess.

Watch the documentary Goddess Remembered (available for free on Youtube) to learn more about the Great Goddess and matrifocal societies of the past, and how the loss of goddess-centric societies can be linked with today's environmental crisis.

*

The snake was held sacred by many ancient cultures, representing the creative life-force, and carrying symbolism of sexuality, fertility, and transformation.

The snake was a symbol of eternal life, since each time it shed its skin it seemed reborn. The Pelasgian myth of creation refers to snakes as the reborn dead. Gliding in and out of holes and caverns in the earth, the serpent also symbolized the underworld. The snake—with its stylized image, the spiral—was seen as the vehicle of immortality, and the image of spontaneous life energy.

Like the snake who sheds its skin and still lives, the Moon births herself from her own darkness, and the womb bleeds periodically without being wounded—all these images were seen as miraculously interconnected transformations.

Great live snakes were everywhere kept in the Goddess’s temples during the Neolithic Age. In wall paintings, reliefs and statues, the Goddess was often represented carrying snakes in her upraised arms or coiled around her. Or, she was imaged as a serpent herself, with a woman’s body and a snake’s head.

Everywhere in world myth and imagery, the Goddess-Creatrix was coupled with the sacred serpent. In Egypt she was the Cobra Goddess; the use of the cobra in her ceremonies and icons was so ancient that the inscribed picture of a cobra preceded the names of all goddesses, and became “the hieroglyphic sign for the word Goddess.” Isis also was pictured as a Serpent Goddess. The Sumerian Mother Goddess was known as the Great Mother Serpent of Heaven. A Venezuelan creation myth related by the native Yaruro indigenous people says: "At first there was nothing. Then Puana the Snake, who came first, created the world and everything in it". The African water spirit Mami Wata is pictured with a snake around her neck. Ancient Celtic and Teutonic goddesses were wrapped with snakes. The Aztecs and Mayas imaged the Goddess as a feathered serpent, or flying snake, a form of dragon. The distribution of the Goddess and her Serpent is global.

When we see this worldwide occurrence of the Goddess and her Serpent, we can see the profound power as well as universality of this cosmological symbol. And we begin to see why monotheistic male-dominated religions were committed to the destruction of the goddess/serpent, vilified by the Babylonians as “primeval chaos”—an image picked up later by the Hebrews and used in the biblical Genesis, where Eve linked with her serpent become the symbols of evil. In Judaism, the serpent was portrayed as Samael, the brother of the “evil” first woman, Lilith. When Old Testament reformers went around destroying images of the serpent—calling them “pagan abominations,” what they were really doing was attacking the primordial Goddess religion. They tried to destroy the world’s original, most widespread, and enduring religion by branding it as evil, and by portraying the Mother Goddess and her snake as the source, not of all life, but of “all wickedness”. Western biblicized peoples have lost their original connection to what the Goddess and her Serpent really meant.

In Africa, statues of women with “snakes issuing from the nostrils” indicated clairvoyant powers, and the snake-hair of Medusa had the same significance. According to Merlin Stone, snake venom injected into people who have previously been immunized against it, had highly hallucinogenic qualities; some venom is chemically similar to mescaline (peyote) or the psilocybin of mushrooms. Reported effects were clairvoyance, extraordinary mental powers, enhanced creativity, prophetic visions, and illumination about the primal processes of existence. As Stone remarks, the sacred snakes kept at the Goddess’s oracular shrines “were perhaps not merely the symbols but actually the instruments through which the experiences of divine revelation were reached.”

Ancient women shamans worldwide were aware of this property of snake venom—and this was one of the recognized meanings of the snake symbols and images inscribed everywhere. Rudolf Steiner, founder of Anthroposophy, spoke of the innate clairvoyant power of ancient humanity, a power lost by “modern man,” who is now unaware of his primordial connection with universal life and its magic energies. Reduced to a mere mechanism, the modern man lives in a void of loneliness and alienation. For it is precisely the astral-lunar region, the psychic world of supersensual perception—called by occultists “the astral serpent”—which hyper-masculinized modern society tells us to destroy, to overcome in the name of a hyper-rational, static, asexual, and mechanistic system.

*

The 1979 installation artwork The Dinner Party by feminist artist Judy Chicago features a place setting for the Snake Goddess. Widely regarded as the first epic feminist artwork, the installation is a symbolic history of women in civilization. It features a massive ceremonial banquet arranged on a triangular table, with 39 elaborate place settings, each commemorating a mythical or historical famous woman, including Virginia Woolf, Susan B. Anthony, Sacagawea, Georgia O'Keefe, Ishtar, and Kali, to name a few.

Each place setting includes a hand-painted china plate, ceramic cutlery, a chalice and a napkin. Each plate depicts a brightly colored, elaborately styled vulva form. The settings rest on intricately embroidered runners, using a variety of needlework styles and techniques.

The runner of the Snake Goddess setting is decorated in ivory and gold, with brown and yellow accent colors. There are gold snakes on the back of the runner, and a snake intertwined in the letter “S” on the runner’s front. The front of the runner echoes the figure of the Snake Goddess, with a flounce that mimics her skirt. Inkle-loom woven strips border the runner and are embroidered with patterns similar to those found in Minoan clothes.

The plate is rooted in vulva imagery found throughout The Dinner Party, and is based on the color-scheme of the Cretan Snake Goddesses statues. Echoing their gold and ivory tones, the plate has four pale yellow arms growing out from a center form, “whose egg-like shapes represent the generative force of the goddess” (Chicago, A Symbol of Our Heritage).

Learn more about The Dinner Party by Judy Chicago.

*

Here, you will find simple earth-based and nature-oriented practices, prompts and rituals that will help you connect with the energy of the Goddess.

**

*

This magical guided journey takes you to a ritual fire in the forest where your ancestor awaits and bears witness to your releasing of all that no longer serves you or what has held you back. Mama Bear will then guide you to the womb of Mother Earth, where you will meet your Spirit Guides, Higher Self, and Power Animal, where they will take you to a magical world full of mystery and remembrance. It is here where you will begin unearthing the long-dormant seeds of your soul that help you to remember who you are. Listen here.

Practice by Dakota Earth Cloud Walker on Insight Timer

*

*

What if we sincerely listened to nature? Nature is a vast resource of wisdom on revealing oneness and uniqueness. Nature teaches us at least three important things in the journey of Generous Listening.

First, nature offers us endless tools to internalize and to practice slowing down, being present in the moment and being open to surprises. Second, through connecting to nature, one develops the skills of humility and compassion for all living beings and becomes conscious of oneness.

Third, nature is always bountiful and generous. Nature teaches us about reciprocity and generous giving. Nature teaches us to weave a web of intimacy and reciprocity with the living world, to see ourselves as one kind of person in a much wider field of relatedness, in which all flourishing is mutual. When we listen to and learn from Nature, we are invited to enter into kinship, a form of relationship that acknowledges the deeper workings of reality by operating on the same principles as the very breath which keeps us alive: reciprocity, emergence, and sensuous awareness.

Practice by Vuslat Foundation

*

Dive deeper into the Snake Goddess, Minoan civilization, feminine spirituality, and the ancient worship of the Great Goddess, with these books, essays and documentaries.

-

✎ Book

‘Mysteries of the Snake Goddess: Art, Desire, and the Forging of History’

by Kenneth Lapatin -

✎ Book

‘Minoans: Life in Bronze Age Crete’

by Rodney Casteldon -

✎ Book

‘The Chalice and the Blade: Our History, Our Future’

by Riane Eisler -

✎ Book

‘When God Was a Woman’

by Merlin Stone -

✎ Book

‘The Great Cosmic Mother’

by Monica Sjoo & Barbara Mor -

✎ Book

‘Goddess in the Grass: Serpentine Mythology and the Great Goddess’

by Linda Foubister -

✎ Book

‘The Goddess and Gods of Old Europe: Myths and Cult Images’

by Marija Gimbutas -

☾ Documentary

‘Goddess Remembered’

by Donna Read -

✎ Book

‘Minoans (Peoples of the Past)’

by J. Lesley Fitton -

✎ Book

‘Minoan and Mycenaen Art’

by Reynold Higgins -

✎ Book

‘The Spiral Dance: A Rebirth of the Ancient Religion of the Great Goddess’

by Starhawk -

✎ Book

‘Primal Myths: Creation Myths Around the World’

by Barbara Sproul -

✎ Book

‘Minotaur: Sir Arthur Evans and the Archaeology of the Minoan Myth’

by J. A. Macgillivray -

✎ Book

‘Return of the Goddess’

by Carol P. Christ -

✎ Book

‘The Goddess: Mythological Images of the Feminine’

by Christine Downing -

✎ Book

‘Lost Goddesses of Early Greece: A Collection of Pre-Hellenic Myths’

by Charlene Spretnak -

☆ Essay

‘Why Women Need the Goddess’

by Carol P. Christ -

✦ Journal Article

‘From Knossos to Kavousi: The Popularizing of the Minoan Palace Goddess’

by Geraldine C. Gesell

Image Credits:

The Palace of Minos (Arthur Evans) • The Dinner Party (Judy Chicago) • Eve temped by the Serpent (William Blake) • Lilith (John Collier) • The Ashmolean Museum • Kulturologia • Andrea Wan